Mending the Urban Fabric: Blight in New Orleans

A February 2008 report from the Bureau of Governmental Research, focusing on the blight situation in New Orleans

Full screen

A Report from the Bureau

of Governmental Research

MENDING THE

URBAN FABRIC

Blight in New Orleans

Part I: Structure & Strategy

FEBRUARY 2008

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR Review Committee

BGR Board of Directors

Henry O’Connor, Jr., Chairman

Arnold B. Baker

James B. Barkate

Officers

Virginia Besthoff

Christian T. Brown

Lynes R. Sloss, Chairman

Pamela M. Bryan

LaToya W. Cantrell

Hans B. Jonassen, Vice Chairman

Joan Coulter

Hans B. Jonassen

Robert W. Brown, Secretary

Mark A. Mayer

Carolyn W. McLellan

Sterling Scott Willis, Treasurer

Lynes R. Sloss

Board Members

Herschel L. Abbott, Jr.

BGR Project Staff

Conrad A. Appel III

Robert C. Baird, Jr.

Janet R. Howard, President

Arnold B. Baker

C. Davin Boldissar, Principal Author

James B. Barkate

Peter Reichard, Production Manager

Virginia Besthoff

Ralph O. Brennan

Christian T. Brown

BGR

Pamela M. Bryan

LaToya W. Cantrell

Joan Coulter

The Bureau of Governmental Research is a private, non-

J. Kelly Duncan

profit, independent research organization dedicated to

Ludovico Feoli

informed public policy making and the effective use of

Hardy B. Fowler

public resources for the improvement of government in

Aimee Adatto Freeman

the New Orleans metropolitan area.

Julie Livaudais George

Roy A. Glapion

This report is available on BGR’s web site, www.bgr.org.

Matthew P. LeCorgne

Mark A. Mayer

Carolyn W. McLellan

Henry O’Connor, Jr.

William A. Oliver

Thomas A. Oreck

Gregory St. Etienne

Madeline D. West

Andrew B. Wisdom

Honorary Board

Bryan Bell

Harry J. Blumenthal, Jr.

Edgar L. Chase III

Louis M. Freeman

Richard W. Freeman, Jr.

Ronald J. French

David Guidry

Paul M. Haygood

Diana M. Lewis

Anne M. Milling

R. King Milling

George H. Porter III

Edward F. Stauss, Jr.

Bureau of Governmental Research

938 Lafayette St., Suite 200

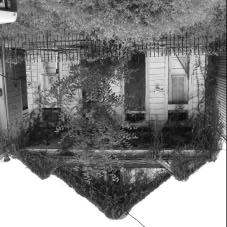

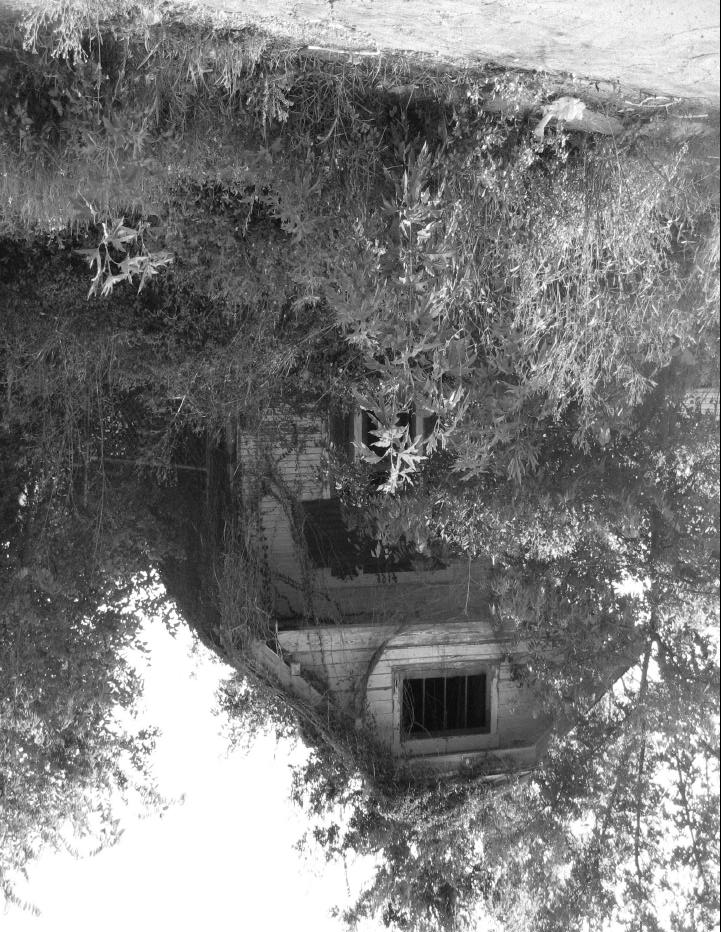

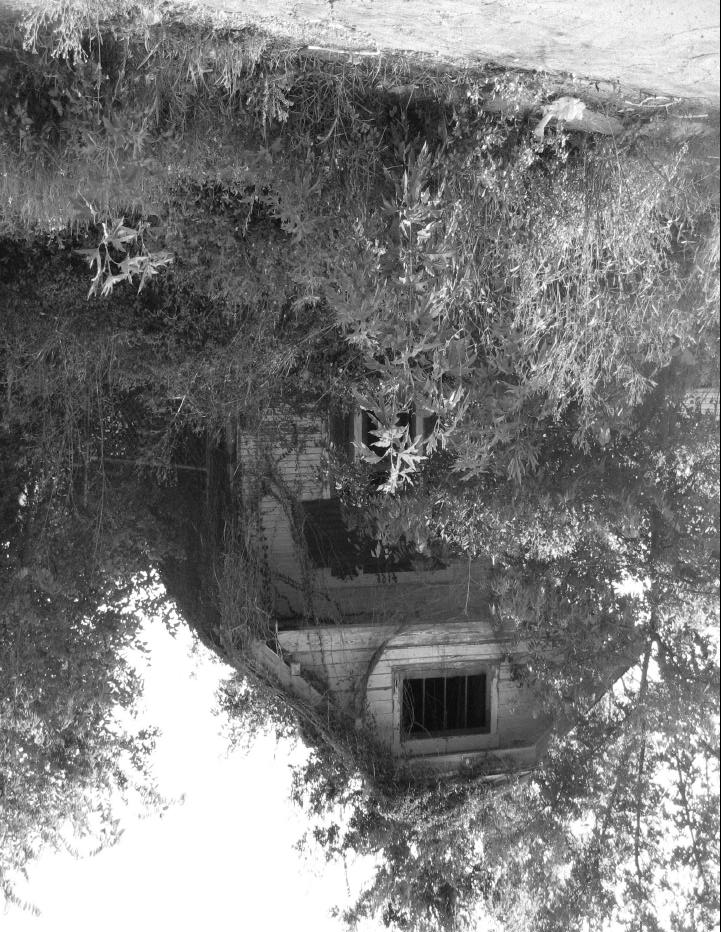

Photos by C. Davin Boldissar

New Orleans, Louisiana 70113

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

INTRODUCTION

1

OVERVIEW OF CHALLENGES

1

PROGRAM STRUCTURE

2

Current Structure

2

Fragmentation Creates Problems

4

Consolidating Blight Management

4

Controls on NORA

5

Code Enforcement: A Citywide Function

5

Coordination

6

GOALS AND STRATEGIES

6

Goals

6

A Comprehensive Citywide Strategy

6

Different Areas, Different Strategies

7

New Orleans’ Strategy

8

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

8

Program Structure

8

Goals and Strategies

9

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

INTRODUCTION

OVERVIEW OF CHALLENGES

ew Orleans has for decades suffered from

New Orleans faces multiple structural, legal and admin-

pervasive blight. Hurricane Katrina and the

istrative problems in addressing blight. They include the

Nresulting levee failures exacerbated this following:

problem. No one has conducted a compre-

hensive survey to determine the number of

n Fragmented Structure. The administration of

blighted properties. However, federal agencies have esti-

blighted property programs in New Orleans is

mated that approximately 80,000 housing units were

fragmented and uncoordinated.

severely damaged by Hurricane Katrina. It is safe to say

that there are tens of thousands of blighted properties in

n Inadequate Goals and Strategies. Local govern-

the city.1

ment has not articulated comprehensive and realis-

tic goals and strategies for redeveloping blighted

Blight poses a serious impediment to the city’s recovery.

property.

Blighted properties destabilize neighborhoods, depress

property values and subject neighbors to health and safe-

n Funding Deficiencies. Blighted property programs

ty hazards. Blight deters investment and increases the

in New Orleans lack sufficient funding to address

likelihood that neighboring properties will also decline

blight effectively.

and become blighted. In post-Katrina New Orleans, it

discourages residents from restoring flood-damaged

n Poor Information. Poor record keeping and a lack

homes. Blight also represents lost tax revenue potential

of access to basic property information impede

in a city with troubled finances.

redevelopment.

Local government plays a key role in fostering blighted

n Acquisition Hurdles. Numerous problems with

property redevelopment. It is uniquely positioned to

acquisition processes prevent redevelopment.

acquire blighted properties and encourage their redevel-

opment, because of its powers, access to funding and

manpower.

METHODOLOGY

BGR conducted interviews with numerous profes-

Unfortunately, New Orleans’ blighted property programs

sionals, including:

have historically been ineffective. In the five years before

Katrina, the City of New Orleans and the New Orleans

n Staff of local government programs in New

Redevelopment Authority (NORA), the entity charged

Orleans and other cities5

with blight remediation in the city, acquired and redevel-

oped only a few hundred properties annually.2 Post-

n Urban planning and land use experts6

Katrina, the only tangible sign of redevelopment has

been the transfer of approximately 600 blighted and tax-

n For-profit and non-profit developers, attorneys

adjudicated properties by NORA and the City to develop-

and observers of the real estate market in New

ers.3

Orleans

BGR has previously made preliminary observations

BGR reviewed reports and academic papers regard-

ing blighted property programs and redevelopment,

regarding the City’s blighted property programs. These

including reports on New Orleans and the cities list-

observations appear in December 2007 letters sent to

ed below. BGR reviewed numerous documents and

NORA and the City’s Office of Recovery Management

materials it obtained from NORA and the City.

(ORM).4 This study builds on BGR’s initial observa-

tions, discussing the obstacles to blight remediation and

In addition to New Orleans’ programs, BGR’s research

proposed solutions in greater detail.

focused on seven widely discussed programs:

Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Louisville,

BGR uses the terms “blight” and “blighted” to refer to

Richmond, Genesee County (containing Flint, Mich.)

severely dilapidated or damaged properties, regardless of

and Baltimore.

whether such properties have been formally designated

as “blighted” under a local government process.

BGR also conducted physical surveys of hundreds of

properties that NORA acquired.7

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR 1

n Disposition Procedures. The procedures for trans-

ferring properties to individuals and developers are

PROPERTY ACQUISITION PROCEDURES

arbitrary, opaque and uncompetitive.

Local government in New Orleans has four pipelines

n Poor Maintenance and Cleanup. NORA has histor-

for acquiring blighted property:

ically not cleaned up and maintained the blighted

property under its control.

Road Home Transfers. The State of Louisiana plans

to transfer to local government bodies residential

n Involuntary Demolitions. Involuntary demolitions,

properties that it purchases through the Road Home

as currently administered, endanger blighted struc-

program. NORA is the designated recipient for the

tures that should be saved and returned to com-

thousands of Road Home properties in New Orleans.

merce.

Expropriation. Expropriation (also called eminent

There is no single “silver bullet” that will solve these

domain) is a basic power of government to take pri-

problems. Instead, policymakers must roll up their

vate property for certain purposes authorized by

sleeves and comprehensively address a multitude of

law, in exchange for compensation. The City and

issues.

NORA both have the power to expropriate blighted

property, although NORA’s powers are narrower.

Due to the complexity and scope of the issues, we are

Expropriation has been severely limited by 2006

addressing them in a two-part report. In this, the first part

amendments to the Louisiana Constitution.8

of that report, we address the first two issues listed

above: program structure and goals and strategies. In the

Tax Adjudication. The City Finance Department

second part, we will address funding and technical and

periodically offers tax delinquent properties for sale

procedural issues relating to property acquisition, main-

to the public. Successful purchasers receive title in

tenance, disposition and demolition.

exchange for payment of back taxes plus costs and

interest.9 The City holds properties that do not sell;

in legal terminology, these properties are “adjudicat-

PROGRAM STRUCTURE

ed” to the City. In many cases, these properties are

blighted.

Local government has a number of tools available to

address blight. It can actively enforce codes, encourage

Lien Foreclosure. The City, through code enforce-

rehabilitation through incentives, demolish properties

ment proceedings, can impose fines and liens on

that pose threats to safety and in some cases force the sale

property that is in violation of public health, housing,

of properties. Often, however, the government must

fire code, environmental or historic district ordi-

acquire blighted properties for ultimate resale or conver-

nances. The City can then foreclose on the lien, forc-

sion to public use.

ing a sale of the property by the Civil Sheriff.10 The

Sheriff sells the property to the highest bidder, which

New Orleans’ blighted property programs, like those in

could be a private party, NORA or the City. The pro-

other cities, focus mainly on the acquisition, maintenance

cedure has not been successfully tested.

and disposition of properties. In New Orleans, govern-

ment can acquire blighted properties through expropria-

tion, tax adjudication and foreclosure on liens created

NORA. NORA is an independent authority created in

through code enforcement proceedings (blight liens). The

1968 for the purpose of “eliminat[ing] and prevent[ing]

Road Home program provides an additional source of

the development or spread of slums and urban blight”

properties. These four acquisition pipelines are described

within New Orleans.11 Although its board members are

in the sidebar at right.

appointed by the mayor from nominees proposed by

State legislators, it is structurally independent from City

government.

Current Structure

NORA has significant powers, including the power to

The administration of the City’s blighted property pro-

undertake large-scale redevelopment and to expropriate

grams is fragmented among a number of entities and

blighted (and, in some cases, nonblighted) properties. In

departments. The following are the key players and their

the decade preceding Hurricane Katrina, NORA’s pri-

roles.

mary activity was the expropriation of blighted proper-

2 BGR

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

55 Properties

Rehabilitated. Of these, 8

appeared to have received

only minimal renovations.

25%

Rehabilitation

48 Properties

42: Redeveloped as new con-

struction affordable housing.

2002 NORA

22%

6: Redeveloped as new con-

Expropriations:

New

struction, either for commercial

Where do they Construction

(4) or market-rate residential

101 Properties

stand?

use (2).

63: Blighted or unmaintained

vacant lots.

46%

7%

31: Maintained vacant lots.

No Redevelopment

Some

7: Contain a blighted structure.

Rehabilitation

15 Properties

Had incomplete rehabilitation

or construction work.

IN 2002, NORA EXPROPRIATED 219 PROPERTIES west of the

Industrial Canal. In May and June, 2007, BGR conducted a site survey

of these properties, identified through records from Orleans Parish Civil

District Court and Orleans Parish Registrar of Conveyances.

ties for resale and redevelopment. The agency had a poor

Unit has managed the sale or donation of the City’s tax

record. In the five years before Katrina, it undertook

adjudicated properties. Recently, it awarded approximately

between 113 and 268 expropriations annually.12 It sold

1,800 tax adjudicated properties to for-profit and nonprofit

most properties to private parties who committed to

developers.14 The City has set aside the remaining 1,500

remediate them. BGR’s survey of year 2002 expropria-

for NORA. The City Attorney’s Office can also use lien

tions indicates that these actions were only partially suc-

foreclosure, although it has never done so successfully.15

cessful. As of mid-2007, almost half of the properties had

not been redeveloped. (See the chart above.)

ORDA. The City recently consolidated several depart-

ments into the Office of Recovery Development and

Since Hurricane Katrina, NORA has been revamped with

Administration (ORDA), under the direction of Edward

an expanded board and new management. It has become

Blakely. The offices that are now part of ORDA include

the designated repository for some blighted properties

(among others):

acquired by other government entities. These include an

estimated 1,500 tax adjudicated properties and the thou-

n Office of Recovery Management. The City created

sands of Road Home properties located in the city.13

ORM in late 2006 as a policy group that formu-

lates recovery and development plans and policies.

City Attorney’s Office Housing Law Unit. The City, acting

It created a recovery plan that calls for specific

primarily through the Housing Law Unit of the City

projects in 17 target zones. These projects include

Attorney’s Office, has also expropriated blighted property

redevelopment of both blighted and non-blighted

for later resale or donation. In addition, the Housing Law

properties in these areas.

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR 3

n Housing Department. The housing department has

Third, fragmentation has contributed to a lack of focus.

a broad range of responsibilities, including the

With the exception of NORA, the personnel of the vari-

administration of federal housing funds and neigh-

ous departments and entities are not dedicated to blight-

borhood education, health care and other social

ed property issues. Rather, blighted property is part of a

service programs. With regard to blighted property

broad portfolio of responsibilities in each agency. The

redevelopment, the department inspects properties

City Attorney’s Office Housing Unit staff works on all

for dangerous conditions and orders involuntary

housing-related issues, including defending the City in

demolitions of structures that pose an imminent

litigation and advising the City on various legal issues.

health threat.16 Working in collaboration with the

Housing department personnel administer a wide range

Department of Safety and Permits, it does the

of federal housing and social services programs. ORDA

same for properties that are in imminent danger of

is responsible for all aspects of recovery management

collapse.17 The housing department is also respon-

and planning, and also has responsibility for housing and

sible for code enforcement and administers the

economic development issues. With these multiple

hearing process for declaring properties blighted.

responsibilities, personnel cannot focus adequately on

Once the City declares a property blighted, the

blighted property issues.

department imposes a fine and a lien to secure

payment. The blight declaration enables NORA or

the City to more easily acquire the property using

Consolidating Blight Management

expropriation, lien foreclosure or tax adjudication.

The solution to these problems begins with the consoli-

n Safety and Permits. The Department of Safety and

dation, to the greatest extent possible, of blighted proper-

Permits, together with the housing department,

ty programs. In particular, one entity should hold, man-

inspects and condemns properties that are in immi-

age and eventually dispose of blighted property. As dis-

nent danger of collapse.

cussed below, this entity could also administer some

aspects of blighted property acquisition.

Other City Departments. Two other City departments

play minor roles in blighted property redevelopment. The

Consolidation of these functions would help facilitate

Health Department, through its environmental health

communication and cooperation. It would put blighted

section, inspects and cites vacant lots for blight. As dis-

property management in the hands of a dedicated staff

cussed above, buildings are inspected and cited by the

with a focus on blighted property issues and make it eas-

housing department. The City Finance Department con-

ier for individuals and entities interested in redeveloping

ducts sales of tax-delinquent properties.

properties to navigate the bureaucracy.

The recommendation to consolidate these functions is

Fragmentation Creates Problems

not new. Earlier reports on blighted property programs in

New Orleans have advocated such consolidation.22

The fragmentation of responsibilities has a long history and

Local governments in other jurisdictions, including

causes three problems. First, the structure is confusing to the

Genesee County, Louisville and Richmond, have also

public and developers. A person concerned about a neigh-

streamlined and consolidated their programs.

bor’s blighted house must navigate several separately

administered and staffed departments and sort through over-

The depository for blighted properties could be either a

lapping and confusing programs. Faced with the frustration

City department or an independent agency. There are,

of working within this structure, many simply give up. 18

however, serious drawbacks to consolidation within City

government. Due to competing demands and responsibil-

Second, coordination among entities and departments

ities, it would be difficult for a City agency to keep focus

has been poor. An analysis prepared for Mayor Nagin’s

and momentum on blight issues. In addition, a City pro-

Transition Team in 2002 stated that “the relevant depart-

gram could wax and wane depending on the politics of

ments do not effectively share information or coordinate

the moment. Also, an independent authority is generally

efforts,” and other reports prepared in 1994 and 2004

subject to more transparency and public participation.

agree.19 In particular, observers have cited failures to

This is because, under the Louisiana Open Meetings

coordinate involuntary demolitions, code enforcement

Law, the authority’s deliberations in board and commit-

and expropriations.20 On more than one occasion, the

tee meetings must be open to the public.23 In contrast,

housing department demolished a structure that NORA

while City Council meetings must be open and public,

was attempting to expropriate for redevelopment.21

deliberations of City departments are not.

4 BGR

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

For these reasons, we believe that blighted property pro-

n NORA’s employees and directors should comply

grams should be formally consolidated in a single-pur-

with conflict-of-interest rules that go beyond exist-

pose authority. NORA is the obvious candidate. Its sole

ing State requirements.

mission is the remediation and redevelopment of blight-

ed properties and areas. It has most of the powers need-

n NORA and the City should jointly establish rigor-

ed to acquire, manage and dispose of blighted property,

ous performance standards.

including access to all of the property pipelines except

lien foreclosure.

n NORA should meet the performance standards

agreed upon with the City.

Since the storm, NORA has become the de facto deposi-

tory for blighted properties. However, the current

Strong performance and accountability could be furthered

arrangement is the result of ad hoc transfers rather than

by oversight from the City’s newly created Office of

the product of a long-term commitment. It should be for-

Inspector General. It is unclear whether the Inspector

malized through a new, comprehensive cooperative

General has sufficient authority to exercise full oversight.

endeavor agreement.

To avoid future disputes over the scope of authority, the

ordinance establishing the office and NORA’s governing

NORA should also, where possible, be the vehicle for

statute should be amended.24

acquiring property. As noted above, it already has the

power to acquire property through expropriation. While

To further increase accountability, the City could retain a

it currently lacks the authority to foreclose on liens, it has

limited right of reversion in properties it transfers to

the ability to purchase property through lien foreclosure. NORA. The right would allow the City to take the prop-

erties back should NORA fail to live up to its legal and

contractual commitments with the City.25 This will

Controls on NORA

require extra paperwork at the time of resale to waive the

right of reversion. To avoid costly delays, the City will

Our recommendation to consolidate functions within

have to execute the waiver in a timely fashion.26

NORA comes with reservations. NORA is not directly

accountable to voters. In addition, it has a troubled histo-

ry and has facilitated the redevelopment of few proper-

Code Enforcement: A Citywide Function

ties. Unless properly managed and monitored, it could

become a vehicle for sweetheart deals or pursue ill-

Code enforcement and involuntary demolitions are basic

advised development schemes that are not in the interest

governmental functions that should remain with the City.

of the city or its neighborhoods.

They should be housed within a single department. Tax

sale administration should also remain with the City

In view of NORA’s troubled history and its independ-

Department of Finance.

ence, controls on NORA’s operations are necessary to

promote strong performance and accountability. At a

In recent years, the housing department has performed

minimum:

the code enforcement and involuntary demolition func-

tions. The administration recently moved that department

n NORA’s efforts should be consistent with the

– and with it code enforcement – into ORDA. ORDA has

City’s master land use plan and its comprehensive

indicated to BGR that the reorganization of City depart-

zoning ordinance.

ments into ORDA reflects a shift from planning to imple-

mentation. The reorganization is expected to facilitate

n NORA should be subject to all maintenance

coordination and cooperation within City government.

requirements and demolition restrictions imposed

on private property owners under State and local

ORDA maintains that its responsibilities are citywide and

law.

that it will be implementing code enforcement citywide on

a strategic basis that is not limited to the 17 target recov-

n NORA and the City should jointly commit to a

ery zones. However, BGR remains concerned that ORDA

specific strategy and procedures for property

may concentrate code enforcement resources too narrowly

acquisition, maintenance and disposition.

on a limited number of recovery projects and areas. This

concern arises from the fact that most of ORDA’s written

n NORA’s activities should incorporate meaningful

public plans and strategy documents focus on the 17 target

public participation.

zones.27 Such a focus would leave fewer resources to

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR 5

address blight in well functioning areas where there is an

which states that NORA’s purpose is to “eliminate and

active real estate market and only scattered blight. These

prevent the development or spread of slums and urban

are the very areas where blight remediation would have an

blight [and] to encourage needed rehabilitation.”29

immediate and critical impact.

Other cities’ blighted property programs also embrace

these basic goals.

Coordination

There are indications that the City and NORA intend to

impose on their blighted property

NORA and the City should careful-

programs other, more expansive

ly coordinate their activities.

goals. These include: building “inclu-

Among other things, coordination

The City and NORA need

sive” or “equitable” communities,

is necessary to ensure that the City

favoring certain types of develop-

to cast a wide net to

will promptly consider and hold

ment, pursuing other social goals

hearings on properties that NORA

encourage development by

such as “green” building, and promot-

is seeking to remediate. It is also

the largest possible group

ing homeownership.30 For example,

necessary to ensure that the City

of individual, non-profit

NORA’s most recent request for pro-

does not demolish buildings for

and for-profit developers.

posals for property disposition

which NORA has renovation plans.

favored developers that intend to do

workforce training, use environmen-

According to ORDA, the City has

tally sustainable techniques, “creat[e]

taken steps to address coordination. The City and NORA

vibrant communities,” use “sustainable ownership” mod-

are meeting regularly to discuss blight remediation

els and produce “projects [that] will be affordable to

issues, and both ORDA and NORA have asserted that

potential purchasers and renters.”31

communication has greatly improved in the last few

months. While internal meetings are certainly important,

The Louisiana Recovery Authority (LRA) and the United

coordination and transparency would be promoted by

States Department of Housing and Urban Development

spelling out responsibilities and procedures in a coopera-

(HUD) impose some restrictions that will require NORA

tive endeavor agreement. Currently, NORA and the City

to pursue goals beyond blight remediation. For example,

have two agreements in effect:28

the LRA requires NORA to redevelop 25% of Road Home

properties into affordable housing.32 However, the City

n In the first agreement, the City committed to allocate

and NORA should focus, to the extent possible within

up to $5 million in federal funds to NORA, on a cost

those parameters, on the basic goal of remediating blight.

reimbursement basis, for property acquisition and

It would be a mistake for NORA and the City to impose

land assembly in designated areas within or around

additional limitations unrelated to that basic goal and

ORDA’s 17 target zones.

good quality development. Such restrictions will limit the

range of potential projects and the pool of interested

n In the second agreement, the City committed to

developers, with the almost certain result that fewer prop-

allocate $2 million in City funds for property acqui-

erties will be rehabilitated.

sition within a target zone surrounding the proposed

Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital site.

To be clear, BGR is not suggesting that developers who

NORA’s property dispositions must comply with a

seek to achieve goals beyond blight remediation — such

concept plan to be jointly agreed upon at a later date. as affordable housing and workforce training — should be

discouraged. Rather, it is simply suggesting that the City

These agreements do not spell out a cohesive strategy or

and NORA should not limit redevelopment to that type of

procedures. They do not provide for performance stan-

development. The City and NORA need to cast a wide net

dards with remedies if NORA fails to meet the standards.

to encourage development by the largest possible group of

individual, non-profit and for-profit developers.

GOALS AND STRATEGIES

A Comprehensive Citywide Strategy

Goals

Because blight is so widespread in New Orleans, the City

The basic goals of a blighted property program are

needs a comprehensive citywide strategy. As NORA has

blight remediation and redevelopment of blighted areas.

acknowledged, given the large number of blighted proper-

This is clearly expressed in NORA’s governing statute,

6 BGR

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

ties in the city and the current state of real estate demand,

In well-functioning areas with an active real estate market

it will be impossible to redevelop all blighted properties in

and only scattered blight, the market-driven approach is

the short term. Therefore, a blight strategy should take into

the most effective. Blighted properties in these areas are

account the viability of different areas and limited avail-

generally out of commerce for property-specific reasons –

able resources. The City and NORA should direct their

such as cloudy title, a vacant succession, or the owner’s

limited resources to viable areas where they would have

absence or intransigence. In well-functioning areas, once

the greatest potential for impact in the near future.

those problems are resolved and the properties are placed

in commerce, redevelopment generally takes place on its

In formulating strategy, local government must recognize

own. Local governments such as Baltimore and Genesee

that it is a facilitator. Individuals and developers will be

County have successfully used this approach. At one time,

the ones who rebuild or rehabilitate blighted homes and

NORA itself used a market-driven strategy in some neigh-

businesses. This is true in every city, no matter how

borhoods, with limited, but positive, results.

extensive the program. Effective blighted property pro-

grams encourage and facilitate private activity.

In more troubled but functioning areas, the targeted

approach is generally the most effective. Such areas have

clusters of blight, in which a critical mass of positive rede-

Different Areas, Different Strategies

velopment is needed. To create the critical mass, develop-

ers need to work on several or many properties at once in

Cities that have pursued successful blight redevelopment

the area. A targeted approach, such as the Neighborhoods in

have used different approaches in different types of

Bloom program in Richmond, Va., enables this.33 The use

areas. Those approaches include:

of a targeted approach should not preclude market-driven

redevelopment efforts in other troubled areas.

n Market-Driven Strategy. The local government

acquires as many blighted properties as possible

In the worst-off areas, which have scattered residents or

and gives all potential developers an equal chance

businesses, total redevelopment is generally the only feasi-

to purchase them.

ble approach. Many communities, including Philadelphia,

Detroit and Pittsburgh, have used this strategy.

n Targeted Strategy. The local government acquires

scattered blighted properties within a target zone

The amount of time and public investment required to

and transfers them to one or more developers for

implement the strategies discussed above varies consid-

immediate redevelopment.

erably. Total redevelopment is the most expensive and

time consuming. The table below provides information

n Total Redevelopment. The local government

on three communities that used that strategy.34

acquires blighted properties within an area to hold

for future large-scale redevelopment. This redevel-

The market-driven strategy is the least expensive and

opment may take the form of a new commercial or

time consuming of the three strategies discussed above.

residential development or a public use, such as a

public park.

Total Redevelopment: A Long and Costly Approach

Community

Type of Redevelopment

Total Subsidies

Time Required to Redevelop

Detroit

Single-family residential neighborhood

At least $115,000 per unit

Still under development (commenced in 1998)

(approximately 300 homes)

Philadelphia

Single- and two-family residential

At least $110,000 per unit

Approximately six years

neighborhood (103 units)

(excluding land acquisition costs)

Pittsburgh

Large sites including derelict steel mills and An average of approximately

10 to 19 years (most projects still under

slag dumps, a stockyard, and a blighted

$250,000 per acre (excluding

development)

neighborhood

infrastructure and construction

subsidies)

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR 7

Buyers provide most or all of the investment. In a well-

would improve the quality of life and increase the hous-

run program, the time required for development of a par-

ing supply with a relatively modest investment of public

ticular property is generally minimal.

resources.

Targeted redevelopment is generally

Total redevelopment should take

Total redevelopment

more expensive than a market-driven

a backseat to the other strategies

projects have a tendency

strategy but less expensive than total

for now. As discussed above, the

redevelopment, both overall and on a

to “suck the oxygen out

costs and time commitment

per-unit basis. The targeted strategy used

the room” and consume all

required for total redevelopment

in Richmond redeveloped 419 properties

available resources, at the

are massive. Also, total redevel-

in seven zones. It cost approximately

expense of other blighted

opment projects have a tendency

$16.6 million (approximately $40,000 in

to “suck the oxygen out the

property redevelopment.

public funds per housing unit). That fig-

room” and consume all avail-

ure includes $2.7 million spent on capi-

able resources, at the expense of

tal improvements such as sidewalks and

other blighted property redevel-

street improvements. Richmond’s targeted redevelop-

opment such as market-driven redevelopment of scat-

ment took approximately four and a half years.35

tered sites. The City’s blighted property programs will

have a wider and much more immediate impact (with

much less cost) by focusing on market-driven and limit-

New Orleans’ Strategy

ed target zone strategies.

NORA and the City intend to rely heavily on a targeted

strategy. That strategy is a small part of a larger recovery

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

plan that involves infrastructure rebuilding, economic

development and redevelopment of vacant and idle prop-

New Orleans has struggled with blight for a long time,

erties in 17 target zones. ORDA has identified seven of

and Hurricane Katrina made the problem worse and more

these zones for blight remediation programs.36 NORA

urgent. To address the problem effectively, local govern-

plans to use a targeted strategy in at least five additional

ment must address a number of structural, legal and

zones.37

administrative challenges. These include fragmented

programs, overly broad goals and the lack of a compre-

The targeted strategy is appropriate for troubled areas.

hensive strategy. In addition, as BGR will discuss in

However, in light of the history of the City’s programs

detail in Part II of this report, funding deficiencies and a

and the slow progress made since Hurricane Katrina, it

host of technical and procedural problems have prevent-

makes sense for the City and NORA to start small, with

ed successful redevelopment. These include poor proper-

a few zones that are feasible and manageable. The num-

ty information, problems with property acquisition and

ber of planned zones is too ambitious at this juncture.

disposition procedures, lack of property maintenance and

NORA and the City should focus, at least at first, on no

a haphazard demolition process.

more than three or four zones.

While these problems may seem daunting, solutions do

In determining which zones to address first, NORA and

exist. To implement them, many policymakers, including

the City should use a transparent public process and clear

City officials, State lawmakers and NORA board and

and limited criteria. Criteria that have been used success-

staff, will have to work together. If these policymakers

fully in other cities to identify such areas include proxim-

roll up their sleeves and comprehensively address the

ity to well-functioning or up-and-coming areas, the

issues, there is a good chance that the City’s troubled

potential to encourage other development, and the pres-

course on blight can be reversed.

ence of existing redevelopment efforts. In New Orleans,

flood protection should also be taken into account in

BGR recommends the following with respect to program

choosing targeted zones.

structure, goals and strategies:

At the same time, the City and NORA should energetical-

Program Structure

ly pursue a market-driven strategy to eliminate blight in

well-functioning areas and in troubled areas where

n Blighted property programs in New Orleans should

be consolidated, to the greatest extent possible, in

appropriate. Addressing blight in functioning areas

NORA. Specifically:

8 BGR

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

o NORA should conduct all expropriations of

o Facilitates private development

blighted properties in New Orleans.

o Directs limited resources to viable areas

o NORA should serve as the depository for

with the greatest potential for impact in the

all blighted properties, with responsibility

near future

for managing and eventually disposing of

them.

o Gives priority to blight remediation efforts

in well-functioning areas and a limited

n City government should retain responsibility for

number of carefully chosen target zones

the administration of tax sales, code enforcement

and involuntary demolitions.

o Relies on a market-driven approach in

areas with sufficient development interest

n The State Legislature should amend NORA’s

enabling legislation:

o Acquires properties within chosen target

areas for simultaneous redevelopment

o To require that NORA follow the City’s

master land use plan and its comprehensive

n When identifying and prioritizing target zones,

zoning ordinance

NORA and the City should use a public process

with clear and limited criteria. Criteria should

o To provide for meaningful public participa-

include proximity to well-functioning and up-and-

tion in NORA’s property acquisition and

coming areas, potential to encourage other devel-

disposition decisions

opment and the presence of existing redevelop-

ment efforts.

o To establish strong conflict-of-interest rules

for NORA’s board members and staff

n The City Council should amend the City ordinance

governing the Office of Inspector General, and

State lawmakers should amend NORA’s enabling

legislation, to clearly give the Office of Inspector

General oversight power over NORA.

n The City and NORA should jointly commit,

through a cooperative endeavor agreement, to the

allocation of responsibilities recommended in this

report and to specific strategies, procedures and

performance standards.

n To provide a means of enforcing NORA’s commit-

ments, the City should retain a clearly defined

right of reversion in properties it transfers to

NORA.

Goals and Strategies

n NORA and the City should focus their blighted

property programs, to the extent possible, on the

goals of blight remediation and good quality rede-

velopment of blighted areas. NORA and the City

should avoid program requirements that interfere

with effective accomplishment of these goals.

n NORA and the City should adopt a comprehensive,

citywide set of strategies that:

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR 9

END NOTES

1 Federal Emergency Management Agency and U.S. Department

6 BGR interviewed experts from University of Michigan,

of Housing and Urban Development, Current Housing Unit

University of Pennsylvania, Virginia Tech, Emory University,

Damage Estimates, Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma,

Johns Hopkins University, Wayne State University and Carnegie

February 12, 2006, p. 23 (estimating that 78,810 housing units

Mellon University.

received “severe” damage from Hurricane Katrina and resulting

flooding). Other sources of data reflecting the scope of the prob-

7 These surveys included all properties west of the Industrial

lem are as follows: Krupa, Michelle, “Doubt Next Door,” The

Canal owned by NORA as of May 2007 or expropriated by NORA

Times-Picayune, August 26, 2007 (blight complaints were made on

in 2002 (NORA’s most active year between 2000 and 2005).

17,112 separate properties between 2006 and July 2007); City of

8

New Orleans, damage assessment data, December 18, 2007,

La. Const. art. I, § 4; La. R.S. 19:136 et seq., La. R.S.

gisweb.cityofno.com/cnogis/dataportal.aspx (post-Katrina damage

33:4720.59, and New Orleans, Louisiana, Ordinance No. 22,643

estimates by municipal address indicate that 29,262 properties had

M.C.S. (May 3, 2007).

damage of 50% or greater); U.S. Department of Housing and

9

Urban Development and U.S. Postal Service, HUD Aggregated

La. R.S. 47:2171 et seq. The purchaser’s title is subject to a

USPS Administrative Data on Address Vacancies, Third Quarter

right of redemption, allowing the original owner a period of time

2007 Data, www.huduser.org/datasets/usps.html (indicating that

to reclaim the property by paying the back taxes, interest and costs.

83,341 addresses in Orleans Parish were vacant or inactive). See

10

also Guillet, Jaime, “New office boosts Blakely’s fight against

La. R.S. 13:2575(C)(1), 2576.

blight,” New Orleans CityBusiness, December 17, 2007 (ORDA

11 La. Acts 1968, No. 170, §§2-3; La. R.S. 33:4720.52-53.

estimate of between 20,000 and 30,000 blighted properties).

12

2

Data from Orleans Parish Civil District Court (indicating 113

Data from Orleans Parish Civil District Court indicates that

actions in 2000; 234 in 2001; 268 in 2002; 212 in 2003; 162 in

NORA filed 113 expropriation suits in 2000, 234 suits in 2001,

2004; and 113 in 2005).

268 suits in 2002, 212 suits in 2003, 162 suits in 2004, and 113

suits in 2005. Some, but not all, of those suits resulted in acquisi-

13 Cooperative Endeavor Agreement between the City of New

tion and redevelopment. The City sold or donated 121 tax adjudi-

Orleans and New Orleans Redevelopment Authority, Contract No.

cated properties to developers between 2000 and Hurricane

K06-594, December 2006, p. 3; minutes from NORA Board of

Katrina. Data received in response to a June 8, 2007, public

Commissioners meeting, April 23, 2007.

records request.

14

3

Data received in response to a June 8, 2007, public records

BGR’s calculations indicate that 607 properties were sold or

request to the City Attorney’s Office (total of 1,833 tax adjudicated

donated by the City and NORA between August 31, 2005, and

properties awarded).

January 18, 2008. These calculations are based on data received in

response to a June 8, 2007, public records request to the City

15 According to the City Attorney’s Office, as of December 2007

Attorney’s Office and on data from the Orleans Parish Registrar of

it had made only one attempt to conduct lien foreclosure, through a

Conveyances.

lawsuit filed in 1997. In that lawsuit, the Court found the City’s

4

attempt procedurally deficient and gave the City a chance to cor-

These letters were dated, respectively, December 3 and

rect those deficiencies. The City did not pursue the case to a con-

December 11, 2007, and are available at BGR’s web site,

clusion. City of New Orleans v. Teche Street, Inc., Case No. 97-

www.bgr.org.

12588 (La. Civil Dist. Ct., Div. “L,” October 20, 1997).

5 BGR interviewed staff from NORA and the following depart-

16 New Orleans, Louisiana, Code § 26-263 (2007).

ments in New Orleans: City Attorney’s Office, Housing

Department, Department of Finance, ORM and ORDA. BGR

17 New Orleans, Louisiana, Code § 26-166 (2007).

interviewed staff from the following programs and entities in other

cities: Philadelphia Neighborhood Transformation Initiative;

18 Past reports have recognized the confusion caused by fragmen-

Pittsburgh Urban Redevelopment Authority; Cleveland Land

tation: National Vacant Properties Campaign, New Orleans

Bank; Louisville Department of Housing and Community

Technical Assessment and Assistance Project, Draft Report:

Development; Richmond Department of Community

Recommended Actions to Improve the Prevention, Acquisition, and

Development; Richmond Federal Reserve Bank; Genesee County

Disposition of New Orleans’ Blighted, Abandoned, and Tax

Land Bank; Baltimore Department of Housing and Community

Adjudicated Properties, October 2004, pp. 1, 5; Mayor Elect C.

Development; Homestead, Fla., Community Redevelopment

Ray Nagin Transition Team, Blighted Housing Task Force Report,

Authority; Detroit Economic Growth Corporation; and Milwaukee

May 2002, p. 22.

Department of Neighborhood Services.

10 BGR

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

END NOTES CONTINUED

19 Mayor Elect C. Ray Nagin Transition Team, op. cit., p. 23;

Redevelopment Authority, July 2007; Mayor C. Ray Nagin,

National Vacant Properties Campaign, op. cit., p. 4 (“There is a

Testimony Before U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee

lack of coordination … which contributes to developer confusion

On Housing And Community Opportunity, February 22, 2007

and a lack of effective targeting by the City.”); Mayor Elect Marc

(City’s blighted property programs “will provide affordable work-

H. Morial Transition Team, April 1994, Report to the Housing Task

force housing units built to community style.”).

Force, p. 5 (“Each organization is subject to unique political con-

31

siderations and pressures which makes collaboration between any

NORA, Request for Qualifications, op. cit. §§ 4-5.

and all of them nearly impossible.”); National Vacant Properties

32 Louisiana Recovery Authority, Action Plan Amendment 14

Campaign, Draft Report, op. cit., p. 4.

(First Allocation) – Road Home Homeowner Compensation Plan,

20 Mayor Elect C. Ray Nagin Transition Team, op. cit., pp. 23, 26.

May 14, 2007, p. 11. See also HUD, Waivers Granted to and

Alternate Requirements for the State of Louisiana’s CDBG

21 See, e.g., NORA v. Ovide, 871 So.2d 396, 398 (La. App. 4 Cir.

Disaster Recovery Grant, 71 Fed. Reg. 34451, 34454 (June 14,

2004).

2006); HUD, Allocations and Common Application and Reporting

Waivers Granted to and Alternate Requirements for the State of

22 Mayor Elect C. Ray Nagin Transition Team, op cit., p. 25;

Louisiana’s CDBG Disaster Recovery Grant, 71 Fed. Reg. 7666,

National Vacant Properties Campaign, New Orleans Technical

7667 (February 13, 2006).

Assessment and Assistance Report: Recommended Actions to

33

Improve the Prevention, Acquisition, and Disposition of New

See, e.g., Galster, George, Peter Tatian and John Accordino,

Orleans’ Blighted, Abandoned, and Tax Adjudicated Properties,

“Targeting Neighborhoods for Neighborhood Revitalization,”

February 2005, pp. 4-5, 9-11 (suggesting that functions could be

Journal of the American Planning Association, Autumn 2006.

consolidated into a new operating entity); Mayor Elect Marc H.

34

Morial Transition Team, op. cit., p. 7.

Interviews with staff from Detroit Economic Growth

Corporation, Philadelphia Neighborhood Transformation Initiative

23 La. R.S. 42:4.1 et seq.

and Pittsburgh Redevelopment Authority.

24

35

The section of the governing ordinance entitled “Authority”

Galster, et al., op. cit., p. 459 n. 9.

gives the Inspector General the authority to investigate depart-

36

ments of “city government.” Other sections of the ordinance gives

ORDA, Target Area Development Plans,

the Inspector General certain powers (such as subpoena powers)

www.nolarecovery.com/taplans.html. These documents also

over independent boards and commissions. New Orleans,

include plans in another area, the Federal City in Algiers, as well

Louisiana Code § 2-1120 (2007).

as a few citywide projects.

25

37

Louisiana law allows sellers to impose a right of reversion. La.

NORA, Parish Redevelopment and Disposition Plan for

C.C. arts. 2567-68; see also, e.g., LeBlanc v. Romero, 783 So.2d

Louisiana Land Trust Properties, December 11, 2007, p. 5;

419, 420 (La. App. 3 Cir. 2001). Applying this restriction to tax

Cooperative Endeavor Agreements (K07-733 and K07-734), op.

adjudicated properties may require changes in law.

cit. (indicating an additional zone surrounding the proposed

Veterans Administration hospital).

26 The purchaser will need this waiver because the right of rever-

sion is a cloud on the purchaser’s title.

27 See, e.g., City of New Orleans 2008 Budget, p. 61 (“The mis-

sion of [ORDA] is to design and successfully implement a plan for

the recovery of the citizens of the City especially in targeted recov-

ery areas….”); ORDA Target Area Development Plans,

www.nolarecovery.com/taplans.html.

28 Cooperative Endeavor Agreements (K07-733 and K07-734)

between City of New Orleans and NORA, December 2007.

29 La. R.S. 33:4720.53.

30 NORA, New Orleans Redevelopment Authority: Restoring,

Rebuilding, and Redeveloping an American City, A Fundraising

and Investment Prospectus, July 2007, pp. 8, 11; NORA, Request

for Qualifications for Participation in “Demonstration Village”

Redevelopment Initiative Conducted by New Orleans

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR 11

Nonprofit Org.

U.S. Postage

PAID

New Orleans, LA

Permit No. 432

Bureau of Governmental Research

938 Lafayette St., Suite 200

New Orleans, Louisiana 70113

CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED

File contents

A Report from the Bureau

of Governmental Research

MENDING THE

URBAN FABRIC

Blight in New Orleans

Part I: Structure & Strategy

FEBRUARY 2008

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR Review Committee

BGR Board of Directors

Henry O’Connor, Jr., Chairman

Arnold B. Baker

James B. Barkate

Officers

Virginia Besthoff

Christian T. Brown

Lynes R. Sloss, Chairman

Pamela M. Bryan

LaToya W. Cantrell

Hans B. Jonassen, Vice Chairman

Joan Coulter

Hans B. Jonassen

Robert W. Brown, Secretary

Mark A. Mayer

Carolyn W. McLellan

Sterling Scott Willis, Treasurer

Lynes R. Sloss

Board Members

Herschel L. Abbott, Jr.

BGR Project Staff

Conrad A. Appel III

Robert C. Baird, Jr.

Janet R. Howard, President

Arnold B. Baker

C. Davin Boldissar, Principal Author

James B. Barkate

Peter Reichard, Production Manager

Virginia Besthoff

Ralph O. Brennan

Christian T. Brown

BGR

Pamela M. Bryan

LaToya W. Cantrell

Joan Coulter

The Bureau of Governmental Research is a private, non-

J. Kelly Duncan

profit, independent research organization dedicated to

Ludovico Feoli

informed public policy making and the effective use of

Hardy B. Fowler

public resources for the improvement of government in

Aimee Adatto Freeman

the New Orleans metropolitan area.

Julie Livaudais George

Roy A. Glapion

This report is available on BGR’s web site, www.bgr.org.

Matthew P. LeCorgne

Mark A. Mayer

Carolyn W. McLellan

Henry O’Connor, Jr.

William A. Oliver

Thomas A. Oreck

Gregory St. Etienne

Madeline D. West

Andrew B. Wisdom

Honorary Board

Bryan Bell

Harry J. Blumenthal, Jr.

Edgar L. Chase III

Louis M. Freeman

Richard W. Freeman, Jr.

Ronald J. French

David Guidry

Paul M. Haygood

Diana M. Lewis

Anne M. Milling

R. King Milling

George H. Porter III

Edward F. Stauss, Jr.

Bureau of Governmental Research

938 Lafayette St., Suite 200

Photos by C. Davin Boldissar

New Orleans, Louisiana 70113

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

INTRODUCTION

1

OVERVIEW OF CHALLENGES

1

PROGRAM STRUCTURE

2

Current Structure

2

Fragmentation Creates Problems

4

Consolidating Blight Management

4

Controls on NORA

5

Code Enforcement: A Citywide Function

5

Coordination

6

GOALS AND STRATEGIES

6

Goals

6

A Comprehensive Citywide Strategy

6

Different Areas, Different Strategies

7

New Orleans’ Strategy

8

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

8

Program Structure

8

Goals and Strategies

9

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

INTRODUCTION

OVERVIEW OF CHALLENGES

ew Orleans has for decades suffered from

New Orleans faces multiple structural, legal and admin-

pervasive blight. Hurricane Katrina and the

istrative problems in addressing blight. They include the

Nresulting levee failures exacerbated this following:

problem. No one has conducted a compre-

hensive survey to determine the number of

n Fragmented Structure. The administration of

blighted properties. However, federal agencies have esti-

blighted property programs in New Orleans is

mated that approximately 80,000 housing units were

fragmented and uncoordinated.

severely damaged by Hurricane Katrina. It is safe to say

that there are tens of thousands of blighted properties in

n Inadequate Goals and Strategies. Local govern-

the city.1

ment has not articulated comprehensive and realis-

tic goals and strategies for redeveloping blighted

Blight poses a serious impediment to the city’s recovery.

property.

Blighted properties destabilize neighborhoods, depress

property values and subject neighbors to health and safe-

n Funding Deficiencies. Blighted property programs

ty hazards. Blight deters investment and increases the

in New Orleans lack sufficient funding to address

likelihood that neighboring properties will also decline

blight effectively.

and become blighted. In post-Katrina New Orleans, it

discourages residents from restoring flood-damaged

n Poor Information. Poor record keeping and a lack

homes. Blight also represents lost tax revenue potential

of access to basic property information impede

in a city with troubled finances.

redevelopment.

Local government plays a key role in fostering blighted

n Acquisition Hurdles. Numerous problems with

property redevelopment. It is uniquely positioned to

acquisition processes prevent redevelopment.

acquire blighted properties and encourage their redevel-

opment, because of its powers, access to funding and

manpower.

METHODOLOGY

BGR conducted interviews with numerous profes-

Unfortunately, New Orleans’ blighted property programs

sionals, including:

have historically been ineffective. In the five years before

Katrina, the City of New Orleans and the New Orleans

n Staff of local government programs in New

Redevelopment Authority (NORA), the entity charged

Orleans and other cities5

with blight remediation in the city, acquired and redevel-

oped only a few hundred properties annually.2 Post-

n Urban planning and land use experts6

Katrina, the only tangible sign of redevelopment has

been the transfer of approximately 600 blighted and tax-

n For-profit and non-profit developers, attorneys

adjudicated properties by NORA and the City to develop-

and observers of the real estate market in New

ers.3

Orleans

BGR has previously made preliminary observations

BGR reviewed reports and academic papers regard-

ing blighted property programs and redevelopment,

regarding the City’s blighted property programs. These

including reports on New Orleans and the cities list-

observations appear in December 2007 letters sent to

ed below. BGR reviewed numerous documents and

NORA and the City’s Office of Recovery Management

materials it obtained from NORA and the City.

(ORM).4 This study builds on BGR’s initial observa-

tions, discussing the obstacles to blight remediation and

In addition to New Orleans’ programs, BGR’s research

proposed solutions in greater detail.

focused on seven widely discussed programs:

Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Louisville,

BGR uses the terms “blight” and “blighted” to refer to

Richmond, Genesee County (containing Flint, Mich.)

severely dilapidated or damaged properties, regardless of

and Baltimore.

whether such properties have been formally designated

as “blighted” under a local government process.

BGR also conducted physical surveys of hundreds of

properties that NORA acquired.7

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR 1

n Disposition Procedures. The procedures for trans-

ferring properties to individuals and developers are

PROPERTY ACQUISITION PROCEDURES

arbitrary, opaque and uncompetitive.

Local government in New Orleans has four pipelines

n Poor Maintenance and Cleanup. NORA has histor-

for acquiring blighted property:

ically not cleaned up and maintained the blighted

property under its control.

Road Home Transfers. The State of Louisiana plans

to transfer to local government bodies residential

n Involuntary Demolitions. Involuntary demolitions,

properties that it purchases through the Road Home

as currently administered, endanger blighted struc-

program. NORA is the designated recipient for the

tures that should be saved and returned to com-

thousands of Road Home properties in New Orleans.

merce.

Expropriation. Expropriation (also called eminent

There is no single “silver bullet” that will solve these

domain) is a basic power of government to take pri-

problems. Instead, policymakers must roll up their

vate property for certain purposes authorized by

sleeves and comprehensively address a multitude of

law, in exchange for compensation. The City and

issues.

NORA both have the power to expropriate blighted

property, although NORA’s powers are narrower.

Due to the complexity and scope of the issues, we are

Expropriation has been severely limited by 2006

addressing them in a two-part report. In this, the first part

amendments to the Louisiana Constitution.8

of that report, we address the first two issues listed

above: program structure and goals and strategies. In the

Tax Adjudication. The City Finance Department

second part, we will address funding and technical and

periodically offers tax delinquent properties for sale

procedural issues relating to property acquisition, main-

to the public. Successful purchasers receive title in

tenance, disposition and demolition.

exchange for payment of back taxes plus costs and

interest.9 The City holds properties that do not sell;

in legal terminology, these properties are “adjudicat-

PROGRAM STRUCTURE

ed” to the City. In many cases, these properties are

blighted.

Local government has a number of tools available to

address blight. It can actively enforce codes, encourage

Lien Foreclosure. The City, through code enforce-

rehabilitation through incentives, demolish properties

ment proceedings, can impose fines and liens on

that pose threats to safety and in some cases force the sale

property that is in violation of public health, housing,

of properties. Often, however, the government must

fire code, environmental or historic district ordi-

acquire blighted properties for ultimate resale or conver-

nances. The City can then foreclose on the lien, forc-

sion to public use.

ing a sale of the property by the Civil Sheriff.10 The

Sheriff sells the property to the highest bidder, which

New Orleans’ blighted property programs, like those in

could be a private party, NORA or the City. The pro-

other cities, focus mainly on the acquisition, maintenance

cedure has not been successfully tested.

and disposition of properties. In New Orleans, govern-

ment can acquire blighted properties through expropria-

tion, tax adjudication and foreclosure on liens created

NORA. NORA is an independent authority created in

through code enforcement proceedings (blight liens). The

1968 for the purpose of “eliminat[ing] and prevent[ing]

Road Home program provides an additional source of

the development or spread of slums and urban blight”

properties. These four acquisition pipelines are described

within New Orleans.11 Although its board members are

in the sidebar at right.

appointed by the mayor from nominees proposed by

State legislators, it is structurally independent from City

government.

Current Structure

NORA has significant powers, including the power to

The administration of the City’s blighted property pro-

undertake large-scale redevelopment and to expropriate

grams is fragmented among a number of entities and

blighted (and, in some cases, nonblighted) properties. In

departments. The following are the key players and their

the decade preceding Hurricane Katrina, NORA’s pri-

roles.

mary activity was the expropriation of blighted proper-

2 BGR

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

55 Properties

Rehabilitated. Of these, 8

appeared to have received

only minimal renovations.

25%

Rehabilitation

48 Properties

42: Redeveloped as new con-

struction affordable housing.

2002 NORA

22%

6: Redeveloped as new con-

Expropriations:

New

struction, either for commercial

Where do they Construction

(4) or market-rate residential

101 Properties

stand?

use (2).

63: Blighted or unmaintained

vacant lots.

46%

7%

31: Maintained vacant lots.

No Redevelopment

Some

7: Contain a blighted structure.

Rehabilitation

15 Properties

Had incomplete rehabilitation

or construction work.

IN 2002, NORA EXPROPRIATED 219 PROPERTIES west of the

Industrial Canal. In May and June, 2007, BGR conducted a site survey

of these properties, identified through records from Orleans Parish Civil

District Court and Orleans Parish Registrar of Conveyances.

ties for resale and redevelopment. The agency had a poor

Unit has managed the sale or donation of the City’s tax

record. In the five years before Katrina, it undertook

adjudicated properties. Recently, it awarded approximately

between 113 and 268 expropriations annually.12 It sold

1,800 tax adjudicated properties to for-profit and nonprofit

most properties to private parties who committed to

developers.14 The City has set aside the remaining 1,500

remediate them. BGR’s survey of year 2002 expropria-

for NORA. The City Attorney’s Office can also use lien

tions indicates that these actions were only partially suc-

foreclosure, although it has never done so successfully.15

cessful. As of mid-2007, almost half of the properties had

not been redeveloped. (See the chart above.)

ORDA. The City recently consolidated several depart-

ments into the Office of Recovery Development and

Since Hurricane Katrina, NORA has been revamped with

Administration (ORDA), under the direction of Edward

an expanded board and new management. It has become

Blakely. The offices that are now part of ORDA include

the designated repository for some blighted properties

(among others):

acquired by other government entities. These include an

estimated 1,500 tax adjudicated properties and the thou-

n Office of Recovery Management. The City created

sands of Road Home properties located in the city.13

ORM in late 2006 as a policy group that formu-

lates recovery and development plans and policies.

City Attorney’s Office Housing Law Unit. The City, acting

It created a recovery plan that calls for specific

primarily through the Housing Law Unit of the City

projects in 17 target zones. These projects include

Attorney’s Office, has also expropriated blighted property

redevelopment of both blighted and non-blighted

for later resale or donation. In addition, the Housing Law

properties in these areas.

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

BGR 3

n Housing Department. The housing department has

Third, fragmentation has contributed to a lack of focus.

a broad range of responsibilities, including the

With the exception of NORA, the personnel of the vari-

administration of federal housing funds and neigh-

ous departments and entities are not dedicated to blight-

borhood education, health care and other social

ed property issues. Rather, blighted property is part of a

service programs. With regard to blighted property

broad portfolio of responsibilities in each agency. The

redevelopment, the department inspects properties

City Attorney’s Office Housing Unit staff works on all

for dangerous conditions and orders involuntary

housing-related issues, including defending the City in

demolitions of structures that pose an imminent

litigation and advising the City on various legal issues.

health threat.16 Working in collaboration with the

Housing department personnel administer a wide range

Department of Safety and Permits, it does the

of federal housing and social services programs. ORDA

same for properties that are in imminent danger of

is responsible for all aspects of recovery management

collapse.17 The housing department is also respon-

and planning, and also has responsibility for housing and

sible for code enforcement and administers the

economic development issues. With these multiple

hearing process for declaring properties blighted.

responsibilities, personnel cannot focus adequately on

Once the City declares a property blighted, the

blighted property issues.

department imposes a fine and a lien to secure

payment. The blight declaration enables NORA or

the City to more easily acquire the property using

Consolidating Blight Management

expropriation, lien foreclosure or tax adjudication.

The solution to these problems begins with the consoli-

n Safety and Permits. The Department of Safety and

dation, to the greatest extent possible, of blighted proper-

Permits, together with the housing department,

ty programs. In particular, one entity should hold, man-

inspects and condemns properties that are in immi-

age and eventually dispose of blighted property. As dis-

nent danger of collapse.

cussed below, this entity could also administer some

aspects of blighted property acquisition.

Other City Departments. Two other City departments

play minor roles in blighted property redevelopment. The

Consolidation of these functions would help facilitate

Health Department, through its environmental health

communication and cooperation. It would put blighted

section, inspects and cites vacant lots for blight. As dis-

property management in the hands of a dedicated staff

cussed above, buildings are inspected and cited by the

with a focus on blighted property issues and make it eas-

housing department. The City Finance Department con-

ier for individuals and entities interested in redeveloping

ducts sales of tax-delinquent properties.

properties to navigate the bureaucracy.

The recommendation to consolidate these functions is

Fragmentation Creates Problems

not new. Earlier reports on blighted property programs in

New Orleans have advocated such consolidation.22

The fragmentation of responsibilities has a long history and

Local governments in other jurisdictions, including

causes three problems. First, the structure is confusing to the

Genesee County, Louisville and Richmond, have also

public and developers. A person concerned about a neigh-

streamlined and consolidated their programs.

bor’s blighted house must navigate several separately

administered and staffed departments and sort through over-

The depository for blighted properties could be either a

lapping and confusing programs. Faced with the frustration

City department or an independent agency. There are,

of working within this structure, many simply give up. 18

however, serious drawbacks to consolidation within City

government. Due to competing demands and responsibil-

Second, coordination among entities and departments

ities, it would be difficult for a City agency to keep focus

has been poor. An analysis prepared for Mayor Nagin’s

and momentum on blight issues. In addition, a City pro-

Transition Team in 2002 stated that “the relevant depart-

gram could wax and wane depending on the politics of

ments do not effectively share information or coordinate

the moment. Also, an independent authority is generally

efforts,” and other reports prepared in 1994 and 2004

subject to more transparency and public participation.

agree.19 In particular, observers have cited failures to

This is because, under the Louisiana Open Meetings

coordinate involuntary demolitions, code enforcement

Law, the authority’s deliberations in board and commit-

and expropriations.20 On more than one occasion, the

tee meetings must be open to the public.23 In contrast,

housing department demolished a structure that NORA

while City Council meetings must be open and public,

was attempting to expropriate for redevelopment.21

deliberations of City departments are not.

4 BGR

MENDING THE URBAN FABRIC

For these reasons, we believe that blighted property pro-

n NORA’s employees and directors should comply

grams should be formally consolidated in a single-pur-

with conflict-of-interest rules that go beyond exist-

pose authority. NORA is the obvious candidate. Its sole

ing State requirements.

mission is the remediation and redevelopment of blight-

ed properties and areas. It has most of the powers need-

n NORA and the City should jointly establish rigor-

ed to acquire, manage and dispose of blighted property,

ous performance standards.

including access to all of the property pipelines except

lien foreclosure.

n NORA should meet the performance standards

agreed upon with the City.

Since the storm, NORA has become the de facto deposi-

tory for blighted properties. However, the current

Strong performance and accountability could be furthered

arrangement is the result of ad hoc transfers rather than

by oversight from the City’s newly created Office of

the product of a long-term commitment. It should be for-

Inspector General. It is unclear whether the Inspector

malized through a new, comprehensive cooperative

General has sufficient authority to exercise full oversight.

endeavor agreement.

To avoid future disputes over the scope of authority, the

ordinance establishing the office and NORA’s governing

NORA should also, where possible, be the vehicle for

statute should be amended.24

acquiring property. As noted above, it already has the

power to acquire property through expropriation. While

To further increase accountability, the City could retain a

it currently lacks the authority to foreclose on liens, it has

limited right of reversion in properties it transfers to

the ability to purchase property through lien foreclosure. NORA. The right would allow the City to take the prop-

erties back should NORA fail to live up to its legal and

contractual commitments with the City.25 This will

Controls on NORA

require extra paperwork at the time of resale to waive the

right of reversion. To avoid costly delays, the City will

Our recommendation to consolidate functions within

have to execute the waiver in a timely fashion.26

NORA comes with reservations. NORA is not directly

accountable to voters. In addition, it has a troubled histo-

ry and has facilitated the redevelopment of few proper-

Code Enforcement: A Citywide Function

ties. Unless properly managed and monitored, it could

become a vehicle for sweetheart deals or pursue ill-

Code enforcement and involuntary demolitions are basic

advised development schemes that are not in the interest

governmental functions that should remain with the City.

of the city or its neighborhoods.

They should be housed within a single department. Tax

sale administration should also remain with the City

In view of NORA’s troubled history and its independ-

Department of Finance.

ence, controls on NORA’s operations are necessary to

promote strong performance and accountability. At a

In recent years, the housing department has performed

minimum:

the code enforcement and involuntary demolition func-

tions. The administration recently moved that department

n NORA’s efforts should be consistent with the

– and with it code enforcement – into ORDA. ORDA has

City’s master land use plan and its comprehensive